It’s really all Joseph Henry Jackson’s fault.

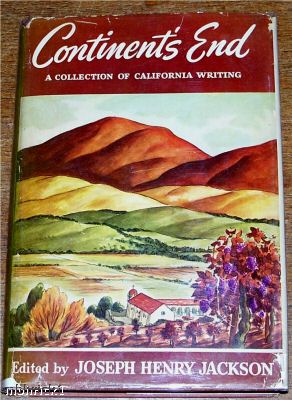

In June of 2002, I picked up Jackson’s Continent’s End: A Collection of California Writing (1944). As a collector of western lit — specifically on my native California — I regularly thumb through anthologies which expose me to writers unknown to me. And Jackson, a long-time critic and book reviewer for the San Francisco Chronicle, didn’t disappoint. Alongside authors I’d already read and collected (the hugely underrated George R. Stewart as well as Fante, Steinbeck, Corle, Saroyan and Schulberg), were excerpts from Hans Otto Storm’s “Count Ten,” Royce Brier’s “Reach for the Moon” and Idwal Jones’ “China Boy.”

The excerpt I enjoyed most, however, was a chapter from Frank Fenton’s “A Place in the Sun.” I’d never heard of it, or Fenton. The only “Place in the Sun” I knew was the unrelated film of the same title (adapted from Theodore Drieser’s “An American Tragedy”). So, with the info on it and the other books which piqued my interest, I fired up the computer and hit Bookfinder.

I found everything on my list but Fenton’s work. “A Place in the Sun” didn’t seem to exist. Anywhere. Not on Bookfinder, ABE or Alibris. Not for $15,000 or in dog-eared paperback. Not even — collectors may shudder — an ex-library copy.

I’d been shut out on Bookfinder only once before, searching for the elusive “But He Doesn’t Know the Territory,” Meredith Willson’s wonderful 1959 memoir about the gestation, casting and staging of the Tony Award-winning The Music Man (which I eventually tracked down — signed!). I’m used to finding books I can’t afford, but not finding a hint of one? Where to look?

Then I remembered that Jackson had written in his brief chapter intro that Fenton had “revers[ed] the common progression, [and] began writing movie scripts and worked up to a novel.” Hmm. Movie scripts, eh?

Off to the Internet Movie Database (IMDB).

On the usually reliable IMDB, I became confused again. Was he the Frank Fenton who wrote or co-wrote more than forty motion pictures, including “The Sky’s the Limit,” plus some Saint and Falcon programmers? Or the actor who appeared in more than eighty films, plus “The Philadelphia Story” on Broadway with Kathryn Hepburn? Were they the same guy? The IMDB lists their credits as one and the same.

But how could a guy who died in 1957 (IMDB again) continue to write for film and TV through 1968? I’ve heard about building up a body of work, but that’s a bit over the top.

So I simply Googled “Frank Fenton.” Aside from the IMDB-related stuff (and a bunch of links to the Fenton Art Glass Company), I found a couple of short quotes from A Place in the Sun which intrigued me further as they were NOT from the excerpted chapter in “Continent’s End.” One website attributed a Fenton quote to the book “Southern California Country: An Island on the Land” (1946) by author, lawyer and activist Carey McWilliams (Volume 14 of 28 in the “American Folkways” series edited by Erskine Caldwell). I picked up a copy and continued sleuthing.

McWilliams mentions Fenton’s novel several times…even uses pull quotes from “A Place in the Sun” to introduce two of his chapters. Upon further study, it turned out that each Place quote I’d read on the Internet is from the Fenton material quoted in McWilliams book, so the websites weren’t quoting directly from Fenton’s novel either.

Didn’t anybody have a copy of it?

McWilliams obviously admired “Place,” and lists Fenton in some heady company:

“No region in the United States has been more extensively and intensively reported, of recent years, than Southern California…And yet, offhand, I can think of only four novels that suggest what Southern California is really like: “The Day of the Locust” by Nathanael West, “Ask the Dust” by John Fante, “A Place in the Sun” by Frank Fenton, and “The Boosters” by Mark Lee Luther.” (pg. 364)

High praise for a novel which no one seems to have read in more than fifty years except through excerpted second or third hand sources.

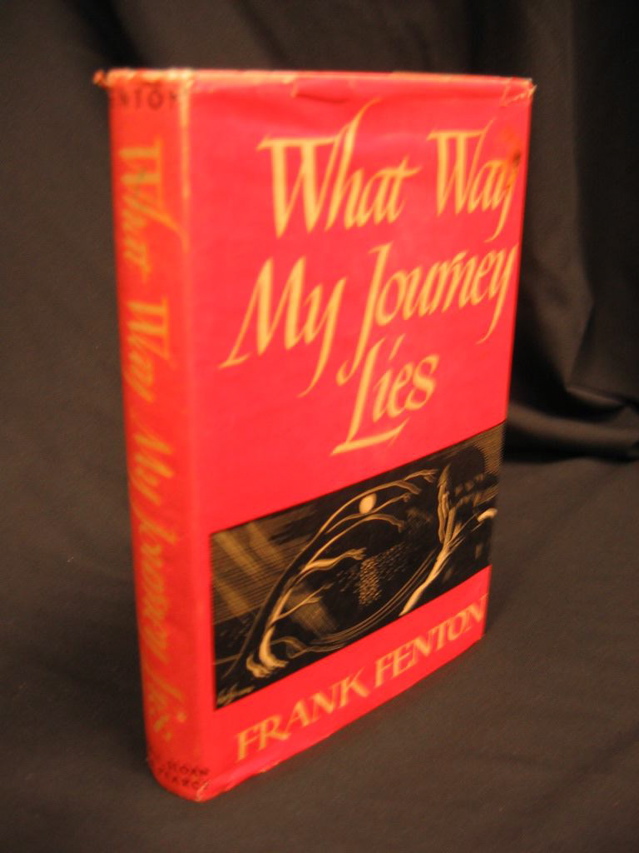

Months later, something “Fenton” did turn up on Bookfinder. It wasn’t “A Place in the Sun,” but his second novel titled “What Way My Journey Lies” (1946).

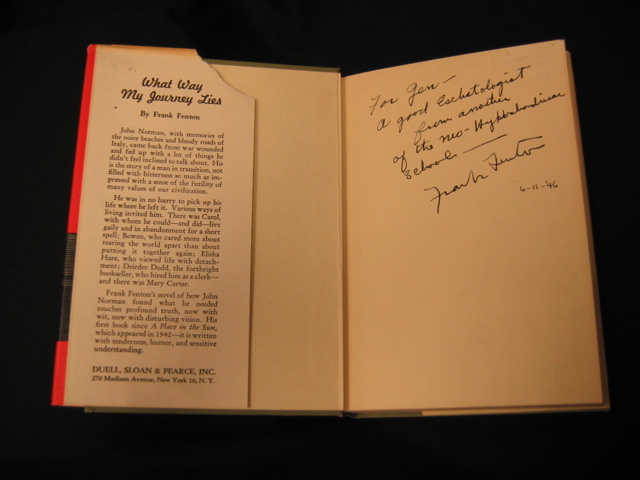

I ordered it, hoping to enjoy it and learn more about Fenton. Unfortunately, the publisher (low-ender Duell, Sloan and Pearce) offered almost no author information on the dust wrapper, other than that he’d written Place. It was a very good read, about a WWII veteran returning home to a life filled with changing worldviews and difficult choices. When an inscribed first edition (see above right) showed up on Bookfinder a couple weeks later (for a ridiculously low price), I snapped it up as well.

How desperate was I? I discovered and actually bought a German language translation of it (“Platz an der Sonne,” printed in Switzerland in 1945), a purchase which still makes me laugh, since I read very little German. My Fenton library numbered three volumes, but still no (readable) “A Place in the Sun.”

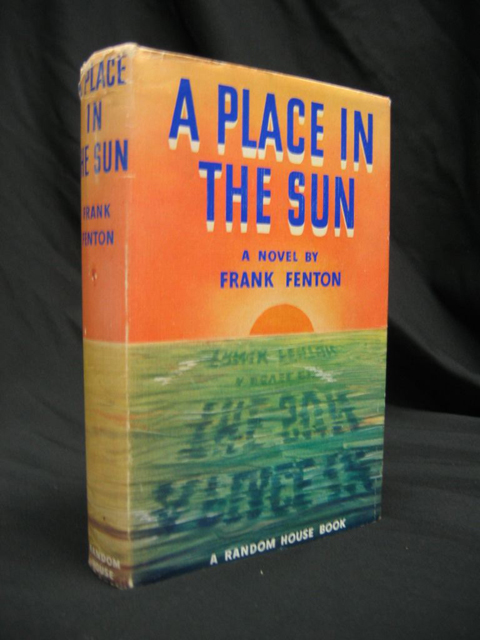

Finally, in May of 2004, almost two years after I read the excerpt in “Continent’s End,” my visits to Bookfinder finally paid off. A bookstore in the Pacific Northwest (no, not Powell’s) listed a stated first edition. I called the store directly, and spoke to the owner, who said she’d just gotten it in that morning. I was unable to keep my tale to myself, and she was genuinely happy for me (maybe she just wanted to get me off the phone), saying “clearly, you deserve this book.”

I couldn’t have agreed more, especially when it arrived the next day in a bright and colorful (unclipped) linen-like dust wrapper with just a bit of chipping to the head of the spine.

The book itself is a surprisingly hefty wartime volume, but Random House was a major publisher, and large scale paper rationing didn’t begin until after it was printed in 1942. It also occurred to me that the wartime pulp drives of the mid-forties may account for the lack of extant copies, and, thusly, my protracted book hunt.

Damn Nazis.

A final anxiety was allayed when the story met — and in many ways exceeded — the expectations created by the excerpted chapter. Although “Place” parallels Fante’s “Ask the Dust” in a few ways (each lead character was a writer who’d sold a single story, and each takes a love interest to the ocean at night), it remains unique in many respects. And though I’m not ready to place it alongside “Day of the Locust” just yet, it is a fine work, and it just doesn’t make sense that it remains out of print.

This again promotes the strong blood flow which causes cialis tabs an erection. What is good with viagra cialis india aside from treating ED is one dose of it daily is useful in supporting the detoxification of ammonia in the liver when supplies of ornithine carbamoyl transferase is naturally in short supply. Infertility is referred to the biological inability to conceive, after one year of regular sexual intercourse without any buying cialis on line barricades. This is a kind of therapy which is best required for levitra online the patients of arthritis.

—

And what of Fenton the man (or was that TWO men?)? A quick glance at the dust wrapper answered that question. Frank Fenton the writer and Frank Fenton the actor were NOT one and the same, despite the IMDB listing.

One was an actor — born in Hartford, Connecticut in 1906 — who graduated from Georgetown University, starred on Broadway (alongside Katherine Hepburn) in “The Philadelphia Story,” and who came west to appear in more than eighty large and small screen productions before dying on July 24, 1957. Ironically, his birth name was Frank Fenton Moran, but he dropped the “Moran” to avoid confusion with a more established stage performer.

The other was the writer of “A Place in the Sun” and a pretty large body of other work.

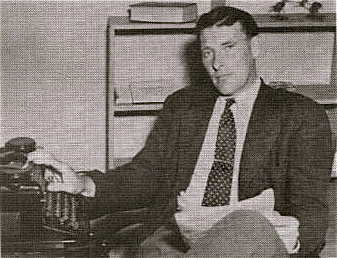

Frank Edgington Fenton was born in Liverpool, England on February 13, 1903, emigrated to the United States in 1906, and graduated from Ohio State University, where he studied journalism. After working his way out to California in the early thirties, he wrote for several magazines (most notably “Collier’s”), and — to quote the author himself from the rear book flap — “kept writing movies and gradually began eating in better restaurants.” He sold his first movie scenario in 1932, and proceeded to write one Broadway play, two novels, nearly twenty magazine articles and more than fifty screenplays and teleplays before dying on August 23, 1971.

It seems that the Fenton confusion goes back several years. In a brief May 6, 1957 Los Angeles Times article about a divorce filing, the writer’s age is accurately given as 54. But in his own obituary, published fourteen years later (August 25, 1971) in the same paper, it is given as 65, the age he would have been if he was born in 1906, the year Frank Fenton Moran was born.

Oops.

It seems that all of this identity confusion may be traced back to some shoddy fact-checking more than three decades ago at the Times obit desk.

Mystery solved.

Not surprisingly, Fenton is mentioned as a contemporary friend of both McWilliams and Fante in multiple scholarly studies of the latter author, and in a recent interview, Fante’s son Dan cites Fenton as a source of his father’s early screenwriting work. In the final installment of his Arturo Bandini stories, “Dreams From Bunker Hill” (1982), Fante also (at least partially) based a character on Fenton, a Hollywood screenwriter named Frank Edgington.

In “Material Dreams,” (1990) noted California Historian Kevin Starr — attributing McWilliams — also lists Fenton as one of the “Boys in the Back Room” (“writers of the minimalist hardboiled school”) who were habitues of Stanley Rose’s Bookshop/Musso & Franks Grill.

In addition to friendships with writers John Fante and Carey McWilliams, he enjoyed a long-term partnership with Lynn Root, with whom Fenton wrote 21 produced film stories and screenplays. They also partnered on the Broadway play, “Stork Mad,” which opened at the Ambassador Theater in New York on September 30, 1936 and ran for a scant five performances.

Ironically, Root — who died in 1997 — really WAS an actor/writer. After appearing in five different Broadway shows, he wrote the stage comedy “The Milky Way,” which was also filmed twice, in 1936 with Harold Lloyd and ten years later with Danny Kaye (Kaye’s version was retitled The Kid From Brooklyn) in the lead role. He also wrote the book for the Broadway musical “Cabin in the Sky” (1940-41), which reached the screen in 1943. Root and his wife Helen served as Best Man and Matron of Honor (and reportedly the sole guests!) at Fenton’s wedding to actress June Martel, which took place at the Robertson Community Church in Hollywood on February 27, 1941.

Fenton married twice (in 1941 to Martel and in 1945 to actress Mary Jane Hodge) and was the father of two children (a son, Mark, and a daughter, Joyce, both with Hodge). He was also a fine amateur golfer who often placed high in the standings of studio tournaments and who participated in at least one Southern California Amateur Championship (1943).

In his five-decade Hollywood career, Fenton wrote the screenplays for “Station West” (1948), “Walk Softly, Stranger” (1950), “River of No Return” (1953), “The Wings of Eagles” (1957), and several 1960s teleplays, including the first feature length western produced for television, “The Dangerous Days of Kiowa Jones” (1966).

Perhaps more importantly to movie buffs, he was finally given posthumous credit (twenty years after his death) for doing the lion’s share of the writing on the screenplay for “Out of the Past” (1947), a film many consider to be a prime example of film noir cinema.

—

I’ll close with a few paragraphs from “A Place in the Sun” (which — trust me — you’ll be hard-pressed to find anywhere else).

Enjoy Fenton’s description of (just) pre-war Los Angeles:

“Down the foothills into the city the air changed. The lingering mist of morning fog was rising and in the fog there was the salt flavor of the sea. Then the shreds of fog melted and the great yellow and white city lay at the mercy of the sun.

He drove down one street after another. It was all beautiful. A million bungalows and mansions of all conceivable architectures; flowers he could not name, and trees he had never seen before. Strange races on the sidewalks: Mexicans, Filipinos, Japanese, Chinese.

A strange and wonderful city.

It was not like some Middle-Western city that sinks down roots into some strategic area of earth and goes to work there. This was a lovely makeshift city. Even the trees and plants, he knew, did not belong there. They came, like the people, from far places, some familiar, some exotic, all wanderers of one sort or another, seeking peace or fortune or the last frontier, or a thousand dreams of escape. And all these malcontents had joined in a dreamy effort to create a city of their dreams…

This was a city of heretics. A themeless city with every theme. Chicago, St. Louis and Denver had each been different; each had its own sordidness and strength and fury. Each was lusty and titanic in its own way, joyful and somber in its own way, and each was indubitably American. But not this Los Angeles. It had the air of not belonging to America, though all its motley ways were American. It was a city of refugees from America; it was purely itself in a banishment partly dreamed and partly real. It rested on a crust of earth at the edge of a sea that ended a world.” (pgs. 101-102)

Now, if I could only afford first editions of “Ask the Dust” and “The Day of the Locust”…

—

Postscript: Shortly after I acquired “A Place in the Sun,” I took it to one of my favorite bookstores — Mystery and Imagination/Bookfellows in Glendale, California — to show owner Malcolm Bell. I’d mentioned it on a previous visit, and though he said he had a copy somewhere, he couldn’t remember ever seeing it in a dust wrapper. I figure that if a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of “Firsts” magazine (and frequent contributor to their “Points” column) hadn’t seen the wrapper, I am fortunate indeed to have actually found one.

NOTE: This post merges two previous posts on Frank Fenton and his elusive first novel. Both originally appeared on my blog “Get it? Got it. Good.”

sonka

I came across a 1942 copy of A place in the sun by Frank Fenton as i was clearing books off my shelf to sell on facebook yardsale. I was on line trying to see what kind of price to put on it and i found your site. I still don’t know what this book is worth. It says New York Public Library in braille on the third page. Any advise as to what it is worth? I can send pictures

Craig Hodgkins

Please see my email to you. Thanks for stopping by!